Jajabara (I)

A journey through whims of fate and lucid memories. Growing up and looking for the purpose of life.

- May 10, 2025

A journey through whims of fate and lucid memories. Growing up and looking for the purpose of life.

Greek mythology is fascinating and full of stories that explore the human condition. My fascination stems from the fact that even gods are flawed - subject to the same emotions and desires as mortals. Zeus is known for his numerous affairs and impulsive decisions, while Hera is often portrayed as jealous and vengeful. Aphhrodite embodies the complexities of love and desire, often leading to chaos and conflict. All divine, yet deeply imperfect.

Sisyphus, the king of Ephyra, was punished by Zeus for cheating death twice. He was condemned to roll a boulder up a hill, only to watch it roll back down, doomed to repeat this task for eternity, never able to complete it. I see the myth of Sisyphus as a metaphor for the futility of life and the eternal journey to find purpose in a world that is indifferent to our existence; a never-ending quest, a journey fraught with constant change and uncertainty. My journey throughout these years feels quite similar. Not because I am being punished by Zeus for cheating death (not that I’d get caught), but because I find myself constantly building a new life in a new corner of the world, pushing a new boulder up a new hill.

Each journey represents a new beginning, a fresh start in a different city, where I build a new life and make new friends. The ascent is filled with hope and possibility. I try to find my place in this newfound world and craft memories before the boulder rolls back down. Signalling the inevitable need to move, leaving behind what I’ve built and starting afresh. Empty houses—ones filled with laughter and joy, shops that let me pay later since I was a regular, now closed, replaced with malls and supermarkets, friends and their stories now only in distant memories, neighbours who became family, and friends who became strangers.

My earliest memories are rooted in Bhubaneswar when I was around two or three years old- dating back to how my room looked, the faint essence of my bed, the tube lights and going to school. My mother’s image isn’t vivid - just fragments of her hair, a white dress, and the stories she told when getting me to sleep. We had an oval mirror in our room, and my faintest memories are looking at her getting ready. She took me everywhere with her, mostly to meet her friends and to her home. I do not remember the fragrance of her perfume, but I remember that I used to love her applying powder on my face.

My father had a Suzuki Max 100. We used to go out on rides, to the beach with his friends, and to places to eat. My parents are foodies, and I was a child who refused to eat anything. I always had this inexplicable urge to sit on the fuel tank. The “shotgun” equivalent of a motorcycle. It makes you feel like a rider, the man in control. My father used to let me sit there, and I remember the wind hitting my face and the thrill of the ride. I loved it. I still do. But now, as an adult, I see how that feeling of control is an illusion. At twenty-five, I see how I wouldn’t want to be the man in control, given a choice. Adulting is hard.

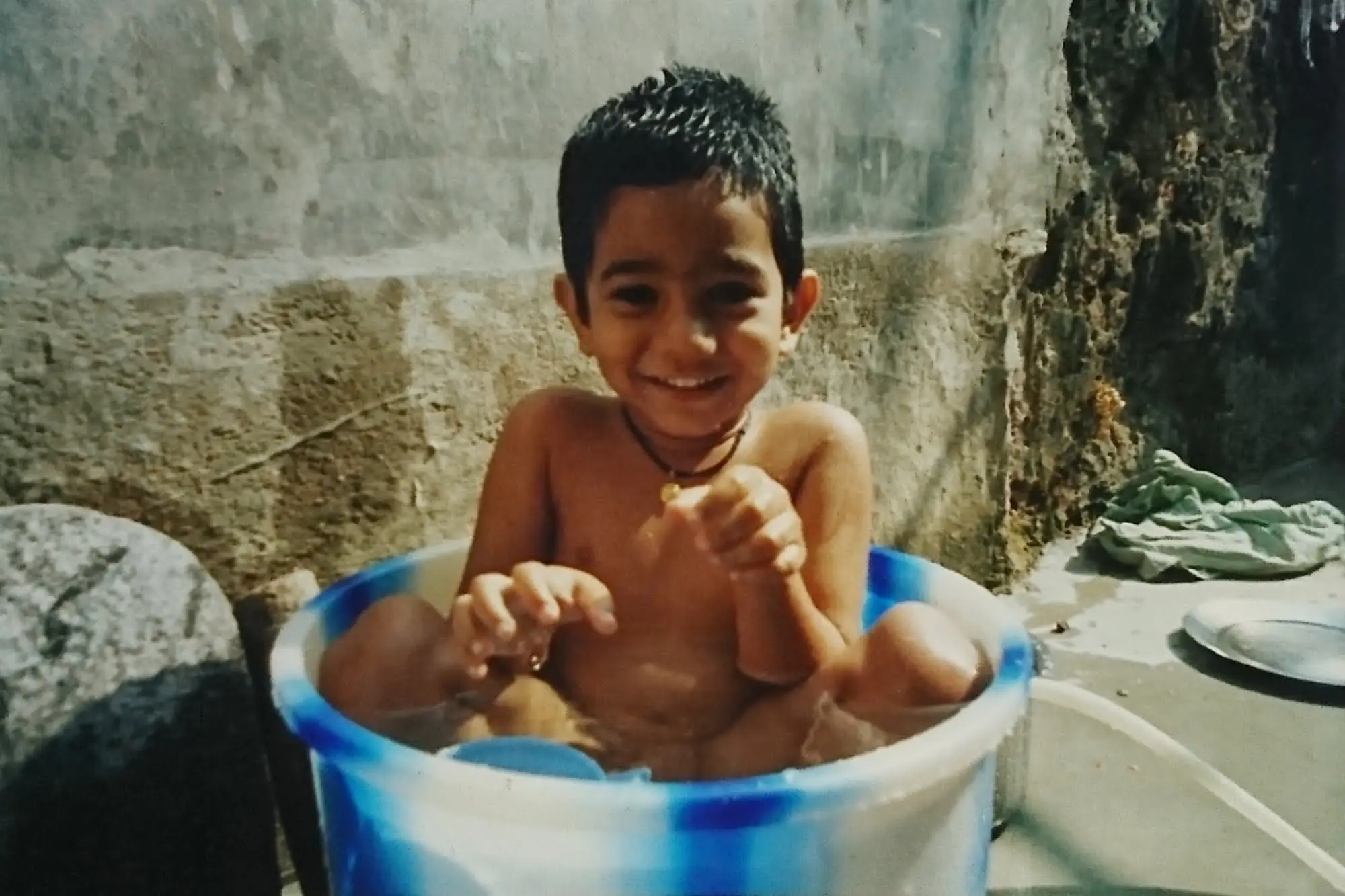

The lucid memories of faint incense sticks, the snug bed I slept in, and the blue tricycle I rode all feel like a different lifetime now, pieces of a world I left behind every time we moved.

Blue, because I remember it was blue, and my cousin-sister had a red one, but she somehow managed to break hers. Our mothers asked us to share the one I had. Sly, that one. Always knew right from wrong, sporting devilish smirks, with a knack for breaking things—chewed, scratched, or demolished in forms beyond recognition. We were colour-coded. All my things, from my tiffin and a huge water bottle to my pencils, were blue. Hers were red.

We are six months apart. Every day, our mothers would pick us up from school, and once we were home, they’d make us sit on the floor for lunch. For reasons I still don’t fully understand, I always took an absurdly long time to finish my meal—it could stretch anywhere from one to three hours. The afternoon naps were floaty and euphoric. We had this incredible Sony music system, and both followed a routine. The same music CD played every afternoon, and we were asleep by the end of the second song. That’s why I could only remember the first couple of songs on the CD, and one of them was Jajabara.

Similar to Sisyphus, Jajabara is a poem about a nomadic lifestyle, with the poet describing his journey through the world, and the world being a stage. The poet refers to their mind as a nomad who constantly roams or seeks something beyond immediate reality. It speaks about the poet’s limitless hopes and indicates a deep longing or an unquenchable thirst for something greater, a cyclical nature of life where values or rules are constantly created and discarded like sandcastles, highlighting the transient, Sisyphean nature of human beliefs. The twenty-five-year-old me relates to it now, the nomadic lifestyle, the constant search for meaning, and the Sisyphean journey of life.

My cousin, who once a child breaking her red tricycle, got married last month. We started as children with colour-coded possessions, and now she is building her own family while I build a career across the ocean in the opposite part of the globe. Strange how nostalgia grips you.

My Sisyphean journey began when my father was transferred from Bhubaneswar to Kolkata in 2005. Each time we packed up and left, I saw the boulder rolling back down. We started building a new life in a different city. The cycle of moving and rebuilding continued, each time leaving behind a piece of myself. Exploring new places and thinking more about the purpose of life.

Leaving behind my grandparents and family was the most difficult. Each of my grandparents had lived for over half a century, carrying a treasury of experiences, perspectives, and philosophies that I loved to listen to. My maternal grandfather worked in the Secretariat, Odisha, while my paternal grandfather had been working in the education department in Odisha. Both of my grandmothers were teachers, though my father’s mother left her profession after marriage, while my mother’s mother continued teaching. Their stories weren’t just simple fables but windows into worlds shaped by time and wisdom. Years later, now that I think of it, the stories make me understand human psychology better. Each scrutinising from their own lens of how the world worked, right or wrong, they were mere perspectives which I seemed to absorb and live through. A time when crossing rivers to attend school and fishing for lunch was the norm. As a child, I was oblivious to the weight of their words, but now, as an adult, I see how their shoes fit me. Leaving my family was the hardest part of moving.

We moved to Kolkata in 2005 when my father’s job took us there. We lived in the company’s quarters in Tollygunge, a small, close-knit space with a single bedroom with an attached balcony that quickly became our new home. Our apartment was on the fourth floor, and the balcony overlooked the entire Kolkata. The colony had just two modest buildings, side by side, separated by a narrow passage that led to a small backyard. At the end of this passage, tucked against the wall, was a bench where you could sit and feel the world slow down. One side was flanked by the buildings, the other by a tall barrier that seemed to enclose our little world.

We couldn’t roam around on our bikes as freely as we used to; the streets of Kolkata felt too busy, the city too vast for us. Luckily, the main road I lived on had a tram stop near the mosque. Trams were slow enough to be safe, yet fascinating enough for me to hang my head out of the window. I remember how the ticket looked, the old paper with a red border, and the sounds of the bells; the bus conductor used to pull a rope tied to the roof, which was connected to a bell. Slowly settling into the busy, loud Kolkata life, the tram rides were a welcome respite, a chance to slow down and watch the world pass by.

A mosque was situated in the middle of the road. I used to figure out play time by listening to the azaan. Four-thirty in the afternoon marked the time for me to rush out and play. The other side of the road was a sweet shop. This one was responsible for sharing all our love with our relatives who came to visit, or the friends and family whom we visited. This shop embodied the essence of Kolkata’s culture.

Kolkata was kind and homely to us. The streets buzzed with busy life, clattering trams, honking yellow taxis, and the vibrant hum of people filling every corner. The smells of street food, especially sweet shops mixed with the scent of incense from nearby temples, and the narrow lanes wound through neighbourhoods like veins through the heart of the city, each turn leading to a different world. It was a world much bigger than what we were used to. The transition was already difficult for us Odias, as we did not understand Bengali, and Kolkata was adamant about making us learn it.

We explored the city mostly by metro, and a trip to a station sparked an odd obsession in me—the escalators. I couldn’t resist them. I’d race up and down in the same one-way belt, completely captivated, much to my father’s chagrin. In those days, corporal punishment was a common disciplinary response to disobedience, and each time I ran wild on the escalator and fell down, every time, I knew what awaited me next. Still, I couldn’t resist the pull of the moving stairs. I had to try and see if I could walk upstairs faster than the escalator moving down. I never could. It’s only now, decades later, that I see how that simple childhood struggle foretold a pattern in my life.

Initially, due to a shift in the middle of an academic year, I was enrolled in a girls’ school, which was a nightmare. Including me, there were four boys in the entire class, and I was the only one who didn’t know Bengali. The next year, we shifted to St. Joseph’s and Mary’s School, and I loved it. I don’t remember anything about it, except that the older boys had their assembly around at 12-1 pm, after we finished our classes, and this one time my principal awarded me a prize for being selected in the IMO. School life had always been good for me, and Kolkata was the beginning of my academic journey.

My sister was born in 2005, and we spent the next year in Kolkata. I’m unsure how I felt about her arrival. I was five and a half. With time, I remember the feeling of having to share my parents with her, which was new and strange, and I was unwilling. A new human being started taking away all my things, which led me to feel annoyed at first. Siblings are territorial, and we were no different. We have some wild stories to tell. I pushed her so hard once that she had to get a stitch on her head. She doesn’t hold that against me anymore, now that I manage to pay her pocket money from time to time.

During this time, our maid used to take care of me. She and her daughter used to babysit me and my sister. She was kind and loving, often shielding me from my mother’s scolding when I refused to study in the evenings, writing down multiplication tables. She even stood up for me when the colony kids bullied me.

That nineteen-year-old evil with a stitched head is now a design student in India, using up all my clothes and my room. She crafts stories and creates art and watches weird shows while eating all the food I used to love. The adulting part of me is now constantly worried about her career, and part of me slightly understands why my parents were constantly fixated on my education and future. It doesn’t justify them, but I see them now. Now that I don’t live with her, I miss her a lot, though I would never admit it to her. I cannot, at any cost, give her the satisfaction of knowing that I miss her.

With my mother having less mobility, I roamed around with my father. Kolkata was a city of yellow taxis, constant honking, and street food. I did not have the same freedom riding my bike as I did in Bhubaneswar, but my father took me everywhere in the metro. Our family and friends visited us regularly, and we often went to the zoo, the Science City, and the Victoria Memorial.

I remember one time I got lost in the Victoria Memorial. My aunt was visiting us, and we went to the Victoria Memorial. I held my father’s hand while gazing at the stars and walking straight. They seemed to follow me as if looking straight at me. I was fascinated by the stars, and I still am. They feel like a nomadic tribe, wandering the sky, telling stories of the past, much like Jajabara. At some point, my father let go of my hand to take out his wallet. Oblivious, I kept walking straight, and when I turned back, I couldn’t see him. I was lost, and an extremely kind family offered me help and asked for my father’s number. They even offered me ice cream, but I was too shaken to eat anything.

Mother never let me go to the Victoria Memorial again. I feel like she had always been my mother in all other worlds—loving, pushing me to get a 100/100 in exams for only God knows what reason, and constantly opposed to whatever I wanted to do because it might be too dangerous, too expensive, or unholy in some way as if God were constantly waiting for me to eat chicken on a Tuesday and punish me for it.

The most memorable part of living in Kolkata would be the train journeys to and from Kolkata to Bhubaneswar. We often visited our home in Bhubaneswar, and I loved the train journeys. The rhythmic sound of the train on the tracks is soothing, and the gentle rocking motion still comforts me while I listen to stories of fellow passengers, living their lives and judging the morality of the world. A time to disconnect from the world and connect with myself, a time to dream, to imagine, and to create.

The train used to halt before entering West Bengal, and my dad would bring food from Kharagpur Station. I feel that the journeys in my life have always been exciting. They helped me live multiple lives, one in Kolkata, and others in the places I visited. During the journey, we halted at various cities, each with different relatives, friends, and stories of their own. Oddly enough, the Indian Railways has a way of making me feel at home.

The transition from Indian Railways to the New York Subway is vivid in my mind, poetic in a way. The boulder, in a different form now, with different stops, 33rd Street, 42nd Street, and 59th Street, as opposed to Balasore, Kharagpur, and Howrah. The train journeys remain the same - a time for introspection.

New York is now my home. Now, I feel like I have always lived here, and the memories of my childhood feel like a distant dream. Turning twenty-five reminds me of the hues of blue I grew up with, the pastel blues of the Indian Railways and the warm blue skies of Bhubaneswar. The blues in New York feel slightly different, colder.

The blue skies remind me of my time in Kolkata, getting lost in the Victoria Memorial, memories of watching Power Rangers, playing too much nintendo, and the tram rides. It reminds me of the food in Kolkata, and the five-year-old me not being able to finish any food. Somewhere in mid-2007, I found myself packed with bags, my mother and cousin’s uncles helping us move with a new boulder this time. This eternal movement in my fate, my Sisyphean journey, was because my father’s job required us to constantly uproot and rebuild in different cities, every two years, as the government mandated it. The following years were spent in Asansol, a small town in West Bengal.