Docking Compilers

Understanding compilers and building binary interpreters for machine code in RISC-V in Hacktoberfest.

- December 12, 2024

Understanding compilers and building binary interpreters for machine code in RISC-V in Hacktoberfest.

This post is the first post in a series of posts on compilers and interpreters. The second post, The Ferryman, introduces compiling high-level languages into machine code instructions, and we attempt at building a working C compiler for RISC-V. This post will delve deeper into the next part; understanding how CPUs execute machine code instructions.

Hacktoberfest is a fantastic opportunity to dive into the world of open source, make meaningful contributions, and sharpen your dev skills. This year, I’m most excited about Yatch: a machine code interpreter for RISC-V written in C++.

Compilers and interpreters are tools that convert high-level programming languages into machine code instructions that the CPU can execute. Compilers translate the entire program into machine code before execution, while interpreters translate and execute the program line by line.

#include <stdio.h>

int main(){

printf("Hello, World!");

return 0;

}

Here’s a brief overview of GCC would compile this program:

#include directive and includes the contents of the stdio.h header file into the program. It also handles macros and other preprocessor directives.Preprocessed Code:

int main(){

printf("Hello, World!");

return 0;

}

Tokens:

int,main,(,),{,printf,(,"Hello, World!",),;,return,0,;,}

FunctionDefinition

├── ReturnType: int

├── FunctionName: main

├── Parameters: ( )

└── Body:

├── ExpressionStatement: printf("Hello, World!");

└── ReturnStatement: return 0;

printf is declared in stdio.h and is correctly used.

The string "Hello, World!" is a valid argument.

The main function correctly returns an integer.

// This is a simplified illustration

function main()

{

tmp0 = "Hello, World!";

call printf(tmp0);

return 0;

}

function main()

{

call printf("Hello, World!");

return 0;

}

Assembly Code (Simplified x86-64 Example):

.section .rodata

.LC0:

.string "Hello, World!"

.text

.globl main

main:

push %rbp

mov %rsp, %rbp

lea .LC0(%rip), %rdi

call puts

mov $0, %eax

pop %rbp

ret

Assembly: The assembler converts the assembly code into object code (machine code in binary form).

Linking: The linker combines object code with libraries to produce the final executable.

For example, for the x86-64 architecture, the conversion in hexadecimal would look like:

# Data Section (.rodata):

01001000 01100101 01101100 01101100 01101111 00101100 00100000 01010111 01101111 01110010 01101100 01100100 00100001 00000000

# Text Section (.text):

01010101 01010101 01010101 01010101 : push %rbp

01001000 10001001 11100101 : mov %rsp, %rbp

01001000 10001101 00111101 **** **** **** **** : lea .LC0(%rip), %rdi

11101000 **** **** **** **** : call puts

10111000 00000000 00000000 00000000 00000000 : mov $0, %eax

01011101 : pop %rbp

11000011 : ret

GCC uses intermediate representations during compilation:

While, interpreters translate and execute the program line by line. The interpreter:

This allows for dynamic typing, interactive debugging, and easier integration with other languages. However, interpreters are generally slower than compilers because they don’t optimize the entire program before execution.

I will finish up a detailed post on a C compiler soon. This post is an intriduction to the next part of the series, a machine code interpreter for RISC-V.

The above generated binary code is run as instructions on the CPU. The CPU executes these instructions in a sequence, and the program runs. The CPU has a set of instructions it can execute, known as the instruction set architecture (ISA). The ISA defines the instructions the CPU can execute, the registers it uses, and the memory model it follows. For example, an instruction might look like 00000000000000000000000010000011, which translates to lb x1, 0(x0) in RISC-V assembly. This instruction, specific to the RISC-V ISA, loads a byte from memory into register x1.

Computer architecture is the design of computer systems, including the CPU, memory, and I/O devices. The CPU executes machine code instructions, which are specific to the CPU architecture. CPU architectures like x86, ARM, and RISC-V have different instruction sets and memory models. Each instruction set has its own assembly language and machine code format.

Here’s why it is important to understand computer architecture: Compilers generate machine code specific to the target CPU architecture. The machine code for x86 is different from ARM or RISC-V. Interpreters, on the other hand, are CPU-independent. They translate high-level code into bytecode or an intermediate representation that can be executed on any platform.

The following post explores machine code instructions and the RISC-V ISA, a popular open-source instruction set architecture. We try to see how a RISC-V CPU would execute machine code instructions using Yatch, a machine code interpreter written in C++.

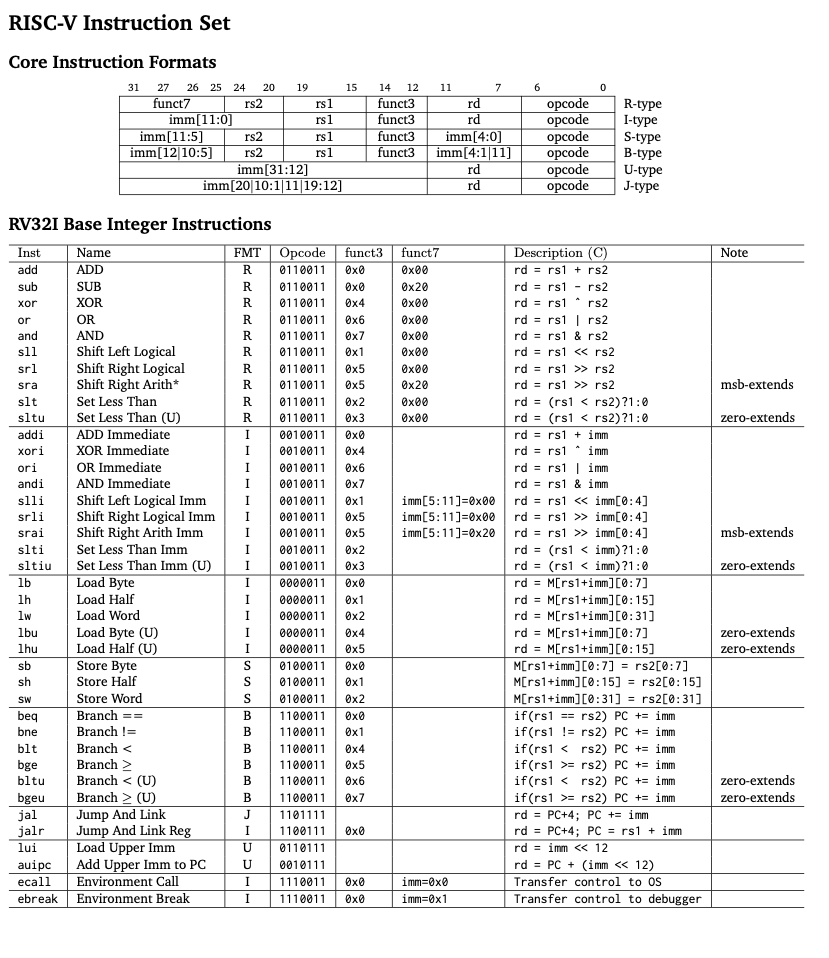

RISC-V is an open-source instruction set architecture (ISA) based on established reduced instruction set computing (RISC) principles. Here is the complete ISA: RISC-V IS Table.

The base ISA consists of approximately 40 instructions, and this project aims to implement most of them. Other instructions sets are extensions to the base ISA, and we might explore them later.

Here is a summary of the base ISA instructions:

The instructions are divided into six categories based on their operation:

A short summary of the RISC-V Card:

Before moving on to the implementation, here’s a small tool that would aid in your understanding of instructions and their working. This tool helps you decode RISCV32I instructions and convert them to their corresponding assembly code. (for example, 00000000000000000000000010000011 to lb x1, 0(x0))

Here is the standalone version of the tool: Barney- A RISC-V Instruction Decoder. This is going to be a handy tool to understand the instructions and their working. The tool will also include decoding assembly code to machine code in the future.( an assembler for RISC-V instructions )

Yatch is a machine code interpreter for RISC-V written in C++. The project aims to provide a basic understanding of how CPUs execute instructions and the principles of pipelining.

To get started with Yatch, you need a C++ compiler. You can use g++ or clang++ to compile the code.

Compile and run the code using the following commands:

$ g++ -std=c++20 -o yatch src/main.cpp

$ ./yatch src/io

The process of executing instructions is divided into five stages:

The main code runs in a loop, it keeps processing instructions until either it encounters a HALT instruction or reaches the end of the program. The interpreter has two main “pipelines” for executing instructions:

The single stage pipeline is used for a simple interpretation of how CPUs execute instructions, and is not actively used in the current implementation. It helps understand the basic principles and builds a foundation for the more complex pipeline.

One instruction is executed at a time. The interpreter fetches the instruction, decodes it, executes it, accesses memory, and writes back the result in a single cycle, repeats the process for the next instruction.

Example: (instruction in memory)

00000000 00000000 00000000 10000011

(data in memory)

01010101 01010101 01010101 01010101

This instruction translates to lb x1, 0(x0) in RISC-V assembly. It loads a byte from memory into register x1. The instruction is executed in the following stages:

Instruction Fetch (IF): The interpreter fetches the instruction from memory. A program counter (PC) keeps track of the current instruction. An instruction in RISC-V is 32 bits long. Yatch stores the instructions in memory as an array of 8-bit integers.

while (getline(imem, line)){

IMem[i] = bitset<8>(line);

i++;

}

....

bitset<32> instruction;

for (int i = 0; i < 4; ++i){

instruction <<= 8; // Shift left by 8 bits to make room for the next byte

instruction |= bitset<32>(IMem[address + i].to_ulong()); // Combine the next byte

// 00000000 00000000 00000000 10000011

}

return instruction;

....

The reason why Yatch stores instructions in memory as an array of 8-bit integers and not 32-bit integers is that the instructions are read from a file, and each line in the file is 8-bits long. However, future implementations might change this.

The program counter (PC) increases by 4 bytes (32 bits) after each instruction.

Instruction Decode (ID): The instruction is decoded and the opcode and operands are extracted. Now, based on the opcode, the interpreter knows which instruction to execute.

Execution (EX): The instruction is executed according to the specific case. For the lb, the interpreter reads the byte from memory and stores it in the destination register.

switch (opcode){

case 0x33:{ // R-type instructions

switch (funct3){

case 0x0:

if (funct7 == 0x00){

result = bitset<32>(myRF.readRF(rs1).to_ulong() + myRF.readRF(rs2).to_ulong()); // ADD

} else if (funct7 == 0x20){

// SUB

.....

case 0x03:{ // I-type instructions

switch (funct3){

case 0x0:

// LB

result = bitset<32>(myRF.readRF(rs1).to_ulong() + imm.to_ulong());

break;

}

}

Memory Access (MEM): Yatch reads the memory from a file and uses an 8-bit array to store the memory. It further uses specific functions to read specific memory locations.

while (getline(dmem, line)){

DMem[i] = bitset<8>(line);

i++;

}

....

bitset<8> readByte(uint32_t address){

if (address < DMem.size())

return DMem[address];

else {

throw runtime_error("Read Byte Error: Address out of bounds."); // Handle out-of-bounds access

return bitset<8>(0);

}

}

The opcode in the example is 0000011, I type the instruction, corresponding to the load instruction. Funct3 is 000, corresponding to the lb instruction. The lb instruction loads a byte from memory into a register. Similarly, a different funct3, for ex. 010 would correspond to the lw instruction, which loads a word from memory into a register. The primary step is to switch on the opcode and execute the corresponding instruction.

Memory is handled using registers. Yatch uses a 32-bit vector to store 32 registers. The instruction loads a byte from memory at the address calculated by adding the immediate offset 0 to the value in register x0 (0). The data in the 0th memory location(01010101) is read and stored in the destination register.

Write Back (WB): The result of the operation is written back to the register file.

Registers. resize(32); // 32 registers in total, each 32 bits wide

Registers[0] = bitset<32>(0); // Register x0 is always 0 in RISC-V

bitset<32> readRF(bitset<5> Reg_addr){

uint32_t reg_index = Reg_addr.to_ulong(); // Converts Reg_addr to integer for indexing

return Registers[reg_index]; // Returns the register value at the given index

}

void writeRF(bitset<5> Reg_addr, bitset<32> Wrt_reg_data){

uint32_t reg_index = Reg_addr.to_ulong(); // Converts Reg_addr to integer for indexing

if (reg_index != 0) Registers[reg_index] = Wrt_reg_data; // Write the data to the register

else throw runtime_error("Cannot write to register x0.");

}

Once all the instructions are executed, the memory is written back to a file.

This entire journey is completed in a single cycle. This serves as a good simulator for understanding how CPUs execute instructions, but the real-world compute requires a more complex pipeline, parallel processing; and multiple instructions executed simultaneously.

A single program has millions of instructions, and executing them one by one would take a lot of time. This pipeline allows the CPU to execute multiple instructions simultaneously, improving the overall performance.

The pipeline is divided into five stages: IF, ID, EX, MEM, and WB. Each stage is responsible for a specific action. The main loop calls these functions in reverse order, starting with the WB stage and ending with the IF stage.

The reverse order achieves to handle hazards. There are three types of hazards: data hazards, structural hazards, and control hazards.

Data hazards occur when instructions that exhibit data dependence modify data in different stages of a pipeline. Ignoring potential data hazards can result in race conditions. Following are the types of data hazards:

read after write (RAW), a true dependency: A read after write (RAW) data hazard refers to a situation where an instruction refers to a result that has not yet been calculated or retrieved. This can occur because even though an instruction is executed after a prior instruction, the prior instruction has been processed only partly through the pipeline. For example:

i1. **R2** <- R5 + R8

i2. R4 <- **R2** + R8

write after read (WAR), an anti-dependency: A write after read (WAR) data hazard refers to a situation where an instruction writes to a register that another instruction reads from. This can occur because the instruction that writes to the register is executed before the instruction that reads from the register. For example:

i1. R4 <- **R2** + R8

i2. **R2** <- R5 + R8

write after write (WAW), an output dependency: A write after write (WAW) data hazard may occur in a concurrent execution environment. It refers to a situation where two instructions are written to the same register. For example:

i1. **R5** <- R4 + R7

i2. **R5** <- R1 + R3

Structural hazards: A structural hazard occurs when two instructions need the same hardware resource at the same time. For example, two instructions need to access the memory at the same time.

Control hazards: A control hazard occurs when the pipeline makes the wrong decision on a branch instruction. The pipeline must be flushed, and the correct instructions must be fetched.

This pipeline is designed to handle control hazards and data hazards. The pipeline initializes the PC, and all the stages except the IF stage are set to NOP (no operation). The IF stage fetches the first instruction from memory and sets the PC to the next instruction.

Example: (instruction in memory)

00000000 00000000 00000000 10000011

(data in memory)

01010101 01010101 01010101 01010101

The main loop calls these functions in reverse order, in the following sequence:

// Initialize pipeline stages to nop

state.IF.nop = false;

state.ID.nop = true;

state.EX.nop = true;

state.MEM.nop = true;

state.WB.nop = true;

// Initialize PC to 0

state.IF.PC = bitset<32>(0);

WB: Write Back: Checks if the instruction has a destination register and writes the result back to the register file.

/* --------------------- WB stage --------------------- */

if (!state.WB.nop){ // Check if the instruction is not a NOP

if (state.WB.wrt_enable){ // Write back to register file

if (state.WB.Wrt_reg_addr.to_ulong() != 0) // x0 is always zero. Cannot override

myRF.writeRF(state.WB.Wrt_reg_addr.to_ulong(), state.WB.Wrt_data); // Write the data to the register

}

}

In the first step, this stage is set as a NOP. In the subsequent steps, the IF stage fetches the instruction from memory and sets the PC to the next instruction. Once the instruction is fetched, the ID stage decodes the instruction and extracts the opcode and operands. The EX stage executes the instruction, and the MEM stage reads or writes data to memory. Finally, the WB stage writes the result back to the register file. The loop continues until the end of the program. (All the stages are NOP)

MEM: Memory Access: Reads or writes data to memory.

if (state.MEM.rd_mem)

{

// Load from memory based on MemOp

uint32_t address = state.MEM.ALUresult.to_ulong(); // Address to read from

bitset<32> memData; // Data read from memory

switch (state.MEM.mem_op) // Check the memory operation

{

case MemLB: // Load Byte

{

bitset<8> data = ext_dmem.readByte(address); // Read a byte from memory

int8_t signed_data = (int8_t)data.to_ulong(); // Convert to signed data

memData = bitset<32>(signed_data); // Store the data in a 32-bit bitset

......

else nextState.WB.Wrt_data = state.MEM.ALUresult; // No memory operation, pass the ALU result to the WB stage.

}

else

nextState.WB.nop = true; // If MEM stage is nop, so WB stage is also nop

In the example, the instruction is a load instruction, so the MEM stage reads data from memory. The data is then passed to the WB stage. The MEM stage also checks if the instruction is a load or store instruction and reads or writes data to memory accordingly. Here,

bitset<32> memData = ext_dmem.readByte(address); // Read a byte from memory

The ALU result is the address of the memory location to read from. The data is then passed on from the ID stage.

EX: Execution: Executes the instruction. The instruction, decoded in the ID stage, is executed here.

if (!state.EX.nop)

{

// Perform ALU operations

bitset<32> operand1 = state.EX.Read_data1; // First operand

bitset<32> operand2 = state.EX.is_I_type ? state.EX.Imm: state.EX.Read_data2; // Second operand

// Forwarding from MEM stage

if (state.MEM.wrt_enable && state.MEM.Wrt_reg_addr.to_ulong() != 0){ // Handles data hazards

if (state.MEM.Wrt_reg_addr == state.EX.Rs)

operand1 = state.MEM.ALUresult; // Forward data from MEM stage to operand1

.......

switch (state.EX.alu_op) // perform ALU operation based on the ALU control signal

{

case ADDU:

ALUresult = bitset<32>(operand1.to_ulong() + operand2.to_ulong());

break;

case SUBU:

ALUresult = bitset<32>(operand1.to_ulong() - operand2.to_ulong());

break;

case AND:

ALUresult = bitset<32>(operand1.to_ulong() & operand2.to_ulong());

break;

.....

The ALU result is calculated based on the opcode and funct3 fields. The result is then passed on to the MEM stage. Our example instruction is a load instruction, so the ALU result is the address of the memory location to read from. The data is then passed on from the ID stage.

ALUresult = bitset<32>(operand1.to_ulong() + operand2.to_ulong()); // calculates the address to read from

ID: Instruction Decode: Decodes the instruction and extracts the opcode and operands.

if (!state.ID.nop){

bitset<32> instruction = state.ID.Instr;

// Decode instruction

uint32_t instr = instruction.to_ulong();

if (instr == 0xFFFFFFFF)

{

// HALT instruction encountered

state.IF.nop = true; // Stop fetching new instructions

nextState.IF.nop = true; // Stop fetching new instructions

}

else{

uint32_t opcode = instr & 0x7F;

uint32_t rd = (instr >> 7) & 0x1F;

uint32_t funct3 = (instr >> 12) & 0x7;

uint32_t rs1 = (instr >> 15) & 0x1F;

uint32_t rs2 = (instr >> 20) & 0x1F;

uint32_t funct7 = (instr >> 25) & 0x7F;

// Hazard Detection

bool stall = false; // Flag to indicate a stall is required

// Check for RAW hazards with EX stage

if (state.EX.rd_mem && state.EX.Wrt_reg_addr.to_ulong() != 0){ // checks if the instruction in EX stage is a load instr and that the writeback register is not x0

if (state.EX.Wrt_reg_addr.to_ulong() == rs1 || state.EX.Wrt_reg_addr.to_ulong() == rs2) stall = true; // Stall required

// handles hazards here

...

if (stall){

nextState.ID = state.ID; // Keep the instruction in the ID stage

nextState.EX.nop = true; // Insert nop in EX stage

nextState.IF = state.IF; // IF stage also needs to stall

// stall helps the EX stage to finish the operation before the ID stage reads the value

}

else{

// Prepare data for EX stage

nextState.EX.nop = false;

nextState.EX.Read_data1 = Read_data1;

nextState.EX.Read_data2 = Read_data2;

nextState.EX.Rs = rs1;

nextState.EX.Rt = rs2;

nextState.EX.Wrt_reg_addr = rd;

nextState.EX.Imm = bitset<32>(signExtendImmediate(instr));

// Set control signals based on opcode

setControlSignals(opcode, funct3, funct7, nextState.EX); // sets the controls for the EX stage to execute the instruction based on the control signals

// Branch Handling

if (opcode == 0x63) // Branch instructions

{

.....

In the example, the instruction is a load instruction, so the ID stage decodes the instruction and extracts the opcode and operands. The ID stage also checks for hazards with the EX stage. If a hazard is detected, the ID stage stalls and waits for the EX stage to finish the operation before reading the value. The ID stage then prepares the data for the EX stage and sets the control signals based on the opcode.

The 0xFFFFFFFF instruction is a placeholder for the HALT instruction. The HALT instruction stops fetching new instructions and halts the program. ID is responsible for HALT detection and handling.

IF: Instruction Fetch: Fetches the instruction from memory.

if (!state.IF.nop){

// Fetch instruction from instruction memory

bitset<32> instruction = ext_imem.readInstr(state.IF.PC);

// Prepare data for ID stage

nextState.ID.nop = false;

nextState.ID.Instr = instruction;

nextState.ID.PC = state.IF.PC;

// Update PC

nextState.IF.PC = bitset<32>(state.IF.PC.to_ulong() + 4); // Fetches the next instruction

}

else

nextState.ID.nop = true; // IF stage is nop, so ID stage is also nop

The IF stage fetches the instruction from memory and sets the PC to the next instruction. The instruction is then passed on to the ID stage. The PC is updated to fetch the next instruction.

While a five-stage pipeline is a correct and realistic representation for many simple RISC-V processors, more advanced implementations can have more stages and additional complexities. The five-stage model remains an effective starting point for understanding pipelining principles and serves as a foundation for more advanced pipeline structures in modern processors.